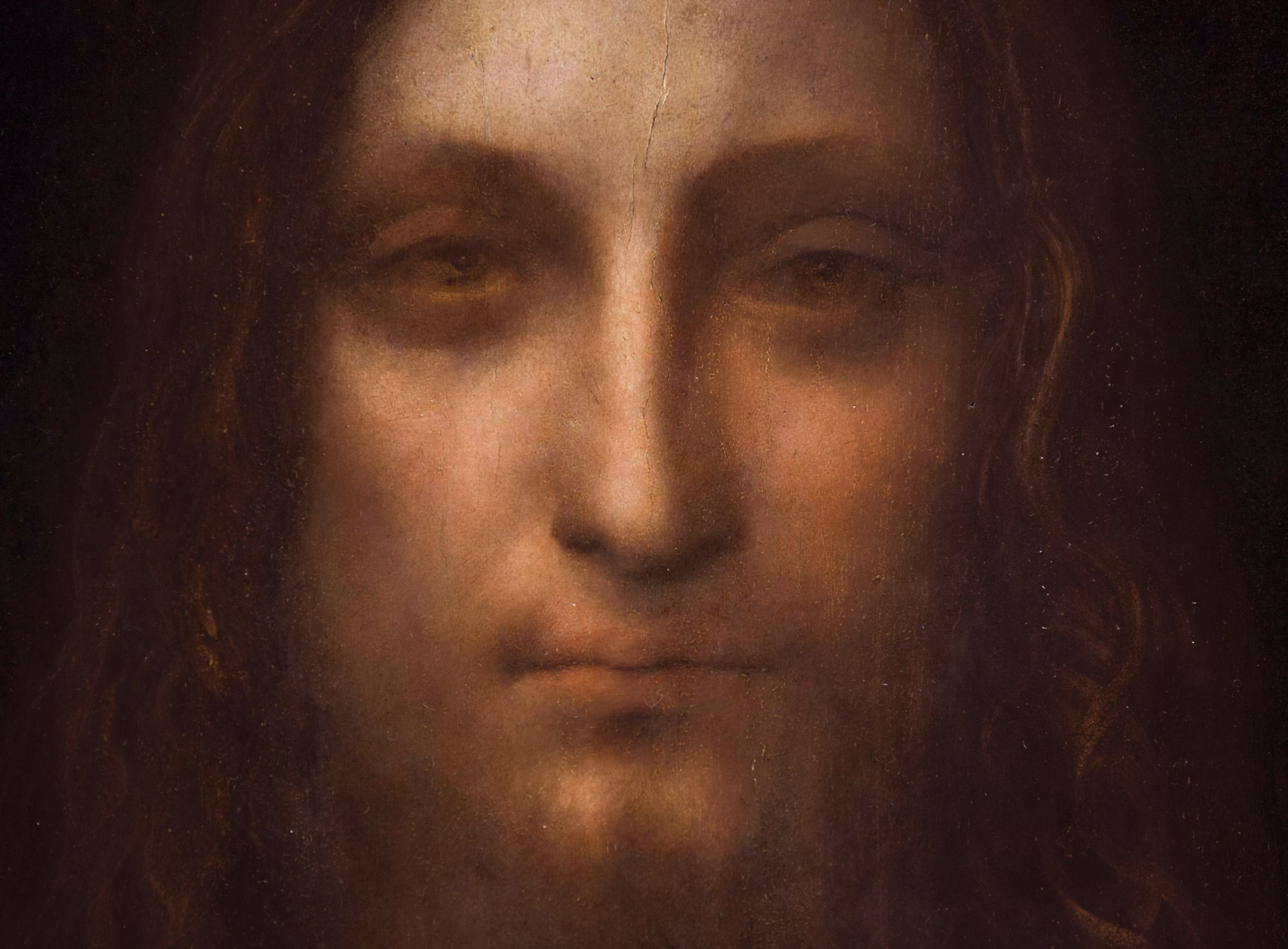

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi shocks the world since its rediscovery in 2005 and restoration in 2007. To top it all off, it has broken the world record for an artwork sold at auction after selling for US$ 450.3 million at Christie’s New York late last year. We delve into the intricate details at possibly “the Last Da Vinci” and figure out why it stunned the world.

Dubbed as the “male Mona Lisa” by the international media, Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi is set to be unveiled on September 18 at the newly opened The Louvre Abu Dhabi. Although the museum has kept its lips sealed over its buyer’s identity, there were a lot of speculations that it was Saudi Arabia’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman who bought it through Prince Badr bin Abdullah, another member of the Saudi royal family.

“Lost and hidden for so long in private hands, Leonardo Da Vinci’s masterpiece is now our gift to the world,” the chairman of Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism Mohamed Khalifa al-Mubarak, said in a statement announcing the public unveiling.

It is indeed a gift to the world. A long, lost gift finally found in new wrappings. A gift befitting of its name “Saviour of the World”, making its long-awaited “Second Coming” at a propitious time for mankind. Being a masterpiece of the famed Renaissance master, people regardless of religion are naturally drawn into it in its recent mini viewings prior to the auction last November. It was not just a representation of the image of Jesus Christ ought to be venerated upon but Da Vinci’s astounding technical masterpiece that is alluring, mesmerising and yet familiar and embracing.

From £45 to $450 million

One little problem with the Salvator Mundi is that it was not dated and signed. But through rigorous tracking done by Christie’s and examination of the Da Vinci scholars, we may strong to assume that the artist painted this around 1500s possibly for King Louis XII of France and his consort Anne of Brittany. With the techniques close to those in Mona Lisa, St. John the Baptist, and The Last Supper, two of Da Vinci’s famous long-surviving masterpieces, scholars believe that the works were contemporaries.