The iconic artist discusses freedom and his ‘useless’ art

'The Mastaba,' Abu Dhabi (Photo: Courtesy of Wolfgang Volz/Christo)

Most artworks are pieces you can look at in the confines of a gallery, a museum, a public square. But for Christo, the projects he calls art take up entire islands. Or mountains. Or parks. “They are urban or rural spaces that we borrow to create a gentle disturbance. That’s it, really. That’s the essence of what we do. Transforming landscapes into something else, for a few days, so that what is in those landscapes is elevated to a work of art.”

See also: In Conversation with Fernando Botero

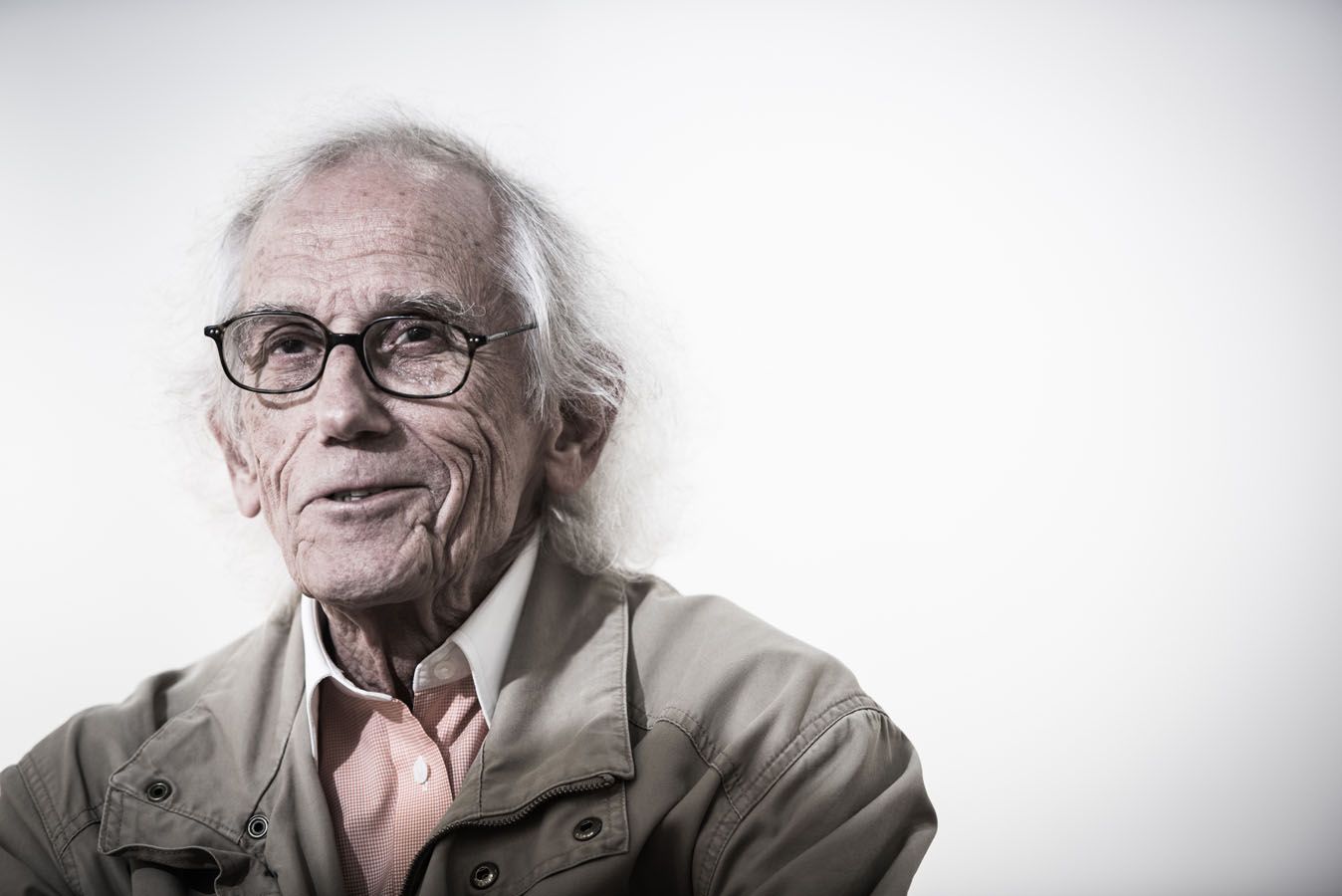

The artist speaks quickly with a thick Bulgarian accent. He’s lean, an almost wiry figure in baggy trousers and a white-collared pink shirt, with messy snow-white hair and a broad, bronzed face marked by deep wrinkles. He’s 81, but you wouldn’t know it: his demeanour is sharp and animated, his replies quick-fire successions of facts, statements and witty comments.

Photo: Moses Ng/Hong Kong Tatler

Born Christo Javacheff in 1935 in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, the artist fled communist Eastern Europe in the 1950s to Paris, where he met his wife and lifelong collaborator, Jeanne-Claude, who died in 2009. The couple soon left France to base themselves in New York, and have worked all around the world in the decades since, making some of the most daring and expensive outdoor art ever seen.

“All our works are useless, in a way, if not for the fact that they are physical traces of our existence. And they bring us joy”

- Christo

They started in 1962 by blocking off Rue Visconti in Paris with a four-metre-high wall of oil barrels in response to the building of the Berlin Wall. Seven years later, they wrapped about 2.4 kilometres of the coastline of Little Bay, Sydney, with a million square feet of synthetic fabric. They went on to plant a forest of umbrellas in rice paddies near Tokyo and along the hillsides of southern California, and in 2005 they placed gates adorned with saffron-coloured panels—7,500 of them—throughout Central Park in New York.

‘The Umbrellas' Japan-US. (Photo: Courtesy of Wolfgang Volz)

Each feat has taken up to decades to complete, costing millions—US$20 million for the Central Park gates, US$26 million for the umbrellas—requiring the labour of hundreds, sometimes thousands of people, and attracting equally mind-boggling numbers of visitors (four million to New York alone in 2005).

See Also: How Artist Simon Birch Turned A Car Park Into a Home

Given their sheer size and ambition, each project has also involved lengthy bureaucratic exchanges with governments, cities and taxpayers. “You don’t get to wrap the Reichstag every day,” Christo quips. “Our work took time and persistence. It all stemmed from an unstoppable urge to realise our vision—and a sense of adventure; we’ve always liked to do things we didn’t know how to do.”

‘Surrounded Islands,’ Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida. (Photo: Courtesy of Wolfgang Volz)

The artist speaks in the past tense because only drawings, pictures and the occasional memento remain of those projects today. “And memory,” he adds. All Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s large-scale installations have been temporary, lasting mere weeks before being dismantled and the materials recycled.

The ephemeral nature of their work is one of the most remarkable aspects of the couple’s oeuvre. It creates a sense of urgency around their projects “because we have had to enjoy and live them in the moment. No wasting time,” Christo says. “We thrive off that immediacy.”

The “we,” of course, refers to him and his wife. Throughout our interview, Christo not only uses the plural form to reminisce on his career, but also to discuss his present works. It strikes me and makes me wonder how his artistic practice has changed since the death of Jeanne-Claude. The couple, who shared the same birthday (June 13, 1935) and a proclivity for using only a first name, worked together as equals for half a century.

‘The Floating Piers,’ Lake Iseo, Italy. (Photo: Courtesy of Wolfgang Volz)

“I miss her very much,” he says. “She was very critical of everything. For every project I am carrying on, I wonder, ‘What would Jeanne-Claude do? What would she say?’” Does he have answers? “Sometimes. I know what she liked and how she thought, so I try to remember that when I work on the projects we started together. After all, she conceived most of them.”

Among those projects was The Floating Piers, which Christo unveiled last year on Lake Iseo, Italy. For 16 days in June, the public could walk for three kilometres on water atop 220,000 floating polyethylene cubes covered in bright orange fabric. It was his first large-scale installation (estimated cost: US$15 million) since the death of Jeanne-Claude, although the couple had been conceptualising it since 1970.

“We have had to enjoy and live our works in the moment. No wasting time. We thrive off that immediacy"

- Christo

“All our works mark the journey of our lives,” he says. “They reflect different moments. They are useless, in a way, if not for the fact that they are physical traces of our existence. And they bring us joy—temporary joy you must soak in while you can, before they [the installations] go.” He pauses. “That’s why we do what we do, and why all our projects are open to everyone, 24 hours a day, with no entry fee: joy, and the freedom that comes with it.”

Read the full story in the May issue of Philippine Tatler.

Like this story? Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get our top stories delivered.