Spearheading the major restoration of the Manila Metropolitan Theatre is the NCCA. Project architects Gerard Lico and Timothy Augustus Ong go into detail on how they will bring an icon back to life

After more than eight decades of existence, the Manila Metropolitan Theatre, a National Cultural Treasure, is undergoing a comprehensive conservation programme under the aegis of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the country’s primary governmental agency tasked with the conservation, promotion, protection, and development of our Filipino historical, cultural, and artistic heritage. As the only existing Art Deco building of its scale and integrity in Asia, the Met is culturally significant in its expression of a Filipinised style of ornamentation that melds indigenous icons and Art Deco elements, creating a stylistic language that resonates with the Filipino.

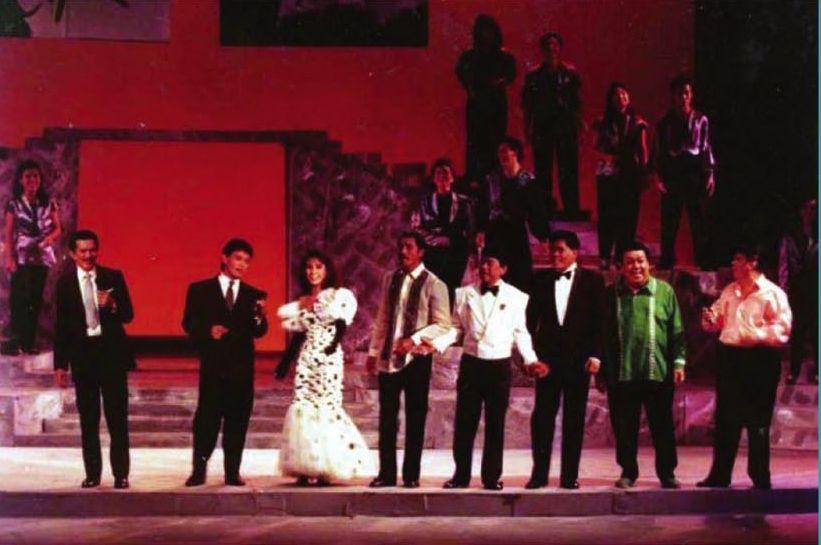

Its historical significance lies in its connection to Filipino pioneers in the arts, with many art and theatre personalities having launched their careers at the Met. Its scale, as the largest theatre then constructed within the Philippines, led the Met to be accepted as the country’s first “national theatre,” hosting cultural performances, social events, and artistic endeavours. As a socio-civic structure, it has been integral in the development of civic pride. Having been funded wholly through private solicitation of the Metropolitan Theatre Company and the support of the Manileños, the Met may be considered as a theatre made by the people, for the people, and owned by the people.

The pioneer Filipino architect Juan M Arellano was commissioned by the government to prepare the blueprints for the Met. He was sent to study the latest technologies in theatre construction in the United States under the tutelage of Thomas W Lamb, who also served as consulting architect for the project. Departing from stately and monochromatic Neoclassicism, Arellano’s aesthetic for the Met was stunningly different from his previous works as it eagerly embraced a fanciful new style: Art Deco. It was an architectural confection fuelled by exoticism and fascination with non-classical ornamentation in the early 20th century.

The architecture of the Met is energised by a mélange of ornaments with allure and fantasy. Arellano adapted the stylistic language of Art Deco which had originated in the Paris Exposition of 1925 to convey local identities and meanings, using native decorative forms and subject matter. He explored familiar native motifs with the aim of asserting cultural independence in colonial social order. The country’s distinct flora and fauna replaced classical ornamentation. Native art provided new forms that were both “exotic” and national that were expressed in vibrant tile ornamentation, stained glass, friezes, sculptures, and wall textures. Nativist iconography is expressed in tell-tale Philippine details such as bamboo banister railings, carved banana and mango reliefs, and batik mosaic patterns. Styled after Philippine vegetation and wildlife, the motifs were executed with the assistance of Arellano’s elder brother Arcadio and Isabelo Tampinco, the leading decorative sculptor of the day.

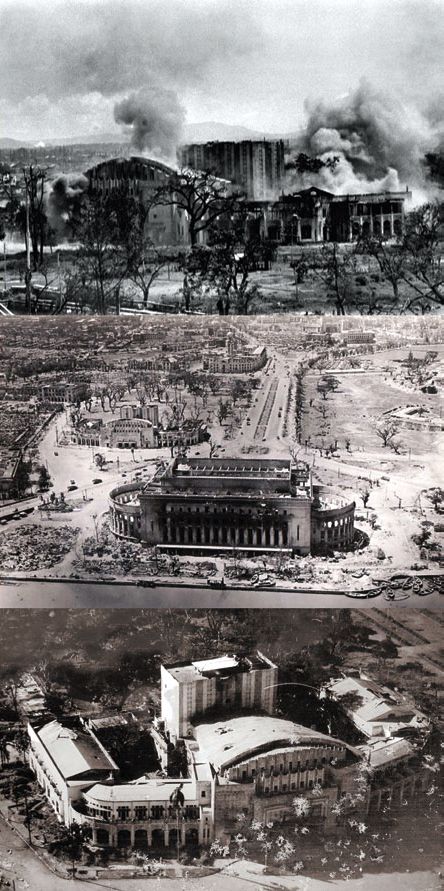

The Met was formally inaugurated on 10 December 1931. Through the next decade, it seemed all the great artists of the world travelling through the Far East were booked to appear at the Met, as the theatre reached the peak of its cultural activities in the years leading up to the war. During the Japanese Occupation, the most important concerts were held there— like the one celebrating the inauguration of the Philippine Republic under Japan on 17 October 1943, that featured Antonino Buenaventura’s Rhapsodetta and Antonio Molina’s arrangement of Rizal’s “Alin Mang Lahi.”

As a cinema palace, the Met was equipped with a modern projector to show both Hollywood and local films. Disney’s Mickey Mouse made his debut in the Philippines here. The Philippines’ legendary LVN Pictures also released its inaugural film, the critically acclaimed Giliw Ko, on 29 July 1939 at the Metropolitan Theatre with no less than President Manuel Quezon attending the premiere.