The strength of a nation is largely built by its connection to its past. With the way the Filipinos are destroying historic landmarks, there seems to be no care for this

This feature story was originally titled as A Lost Heritage, and was published in the August 2013 issue of Tatler Philippines

The built environment, what is defined as the human ordering of the natural world, is a monument to man’s creativity and artistry. The presence of the past embodied in structures built by our ancestors enriches our lives and enlarges our understanding of history while creating for us a sense of continuity. In a changing world the presence of familiar and beautiful landmarks imparts a sense of security, of timelessness. In the same manner that we cherish childhood toys or old photographs because of the memories they evoke, the preservation of historic structures and landscapes protects the nation’s memories by conserving a part of its past.

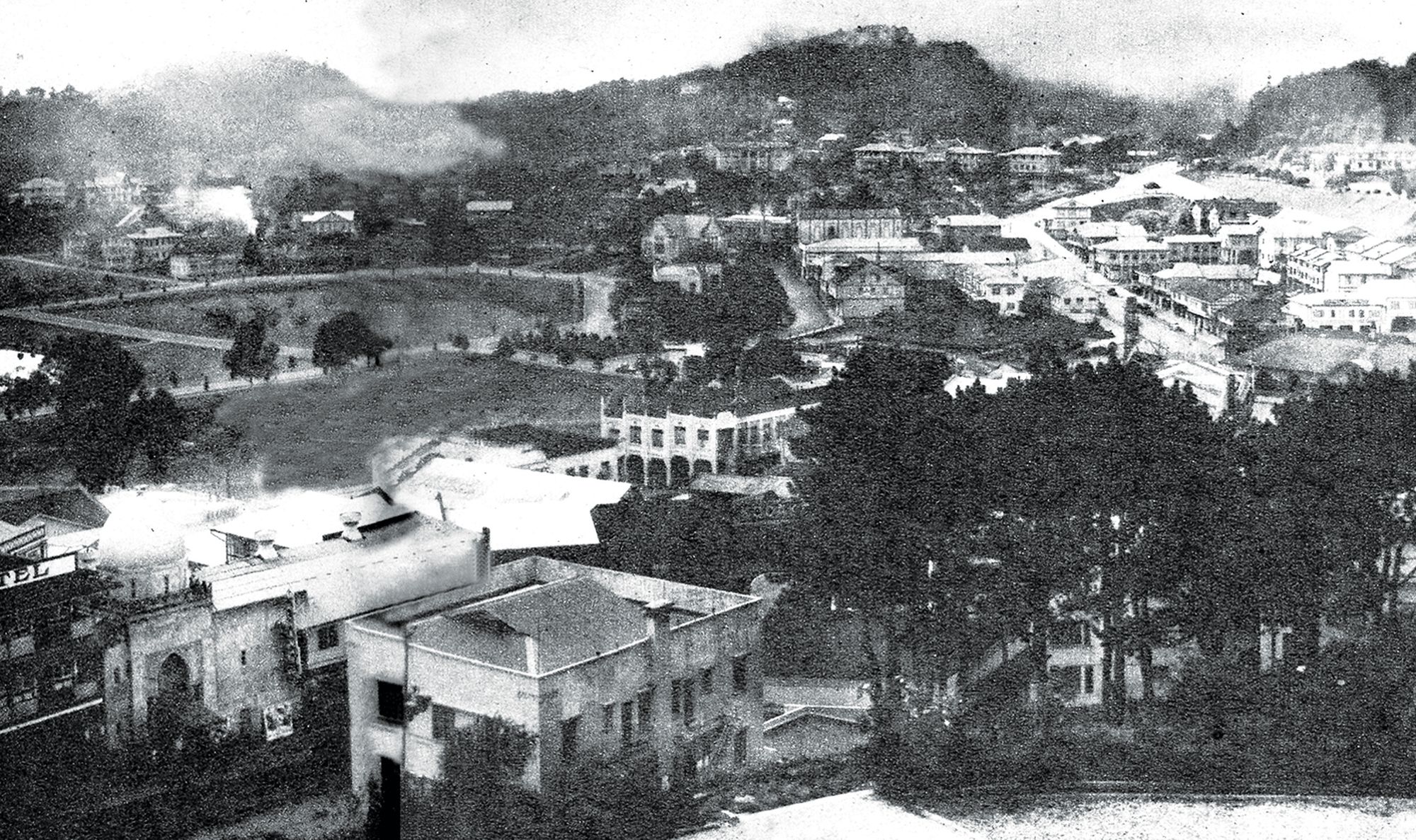

When Spain sold the Philippines to the United States in 1898 it left behind the walled city of Intramuros with 11 churches and chapels, numerous stone fortifications scattered throughout the islands, a Pontifical university older than Harvard and a distinct style of architecture native to the country—found nowhere else. While World War II destroyed the centuries-old Intramuros, it missed some buildings and significant structures in Manila and its old suburbs of Binondo, Sta Cruz, Sta Ana, Paco, Malate and Ermita.

Unfortunately, what the war inadvertently preserved, modernity and a dwindling sense of history razed to the ground.

Can any visitor to Binondo these days honestly find evidence that this is a district established towards the end of the 16th century? Here is a historic district that has been converted from a colonial suburb with significant structures—that included the Hotel Oriente where our national hero, Dr Jose Rizal, stayed before leaving for Europe—into an area with a sense of “nowhere.”

The second half of the 20th century saw the demolition of houses where members of the Rizal family lived, the building on Azcarraga (now Recto) where the Katipunan was established, 19th-century industrial structures, retail establishments, tribunals, colonial theatres all humbled into dust. All these are gone much to the impoverishment of our patrimony and consequently the development of our identity as Filipinos. In its place are blocks of ordinary, concrete high-rises totally unrelated to the city’s historic past.

LOST LANDMARKS

We have wiped out the connection of the city and its suburbs to its antecedents. Preservation of these historic structures would have provided us with opportunities to give meaning and colour to the lessons of our history.

Undoubtedly the demands of development and the exigencies of the bottom line have extracted a heavy toll on historic sites in our urbanscape. Bland, generic skyscrapers have replaced masterpieces by pre-eminent Filipino architects. Urban districts and provincial towns have lost that sense of place because there seems to be a meek acceptance that anything new is automatically better than anything old.

Manila was once described as “the Pearl of the Orient” but very little of its old grandeur exists. Even its landmark boulevard will soon be a back street if the city council succeeds in allowing the reclamation of the waters in front of Malate Church.

The past decades have not been very kind to the preservation of Manila’s historic districts whose structures are increasingly standardised. Most of its architecturally important buildings have bit the dust only to be replaced by homogenous skyscrapers totally out of proportion to the size of the property and narrowness of the streets.

Works by famous Filipino architects from Andres Luna San Pedro to Leandro Locsin have fallen victim to the wrecker’s ball with nary a protest from the government or private sector. We have watched the demolition of buildings like the Jai-Alai and the Paco Railway Station, completed in 1915 by William Parsons. The consulting architect to the American colonial government, Parsons also designed the Manila Hotel, Baguio Mansion House, Philippine General Hospital, and the Opera House where the first Philippine Assembly was inaugurated in 1907.

We have seen the disappearance of the Ideal, Avenue, and State theatres designed by prominent architects Juan Nakpil and Pablo Antonio. Countless 19th-century bahay na bato (architectural style native to the Philippines, with main features like a stone ground floor used for storage and a hard-wood second floor for residence built with wrap-around capiz windows to withstand tropical heat and floods) have been torn apart, sold for scrap, and effaced without regard for their historic significance.