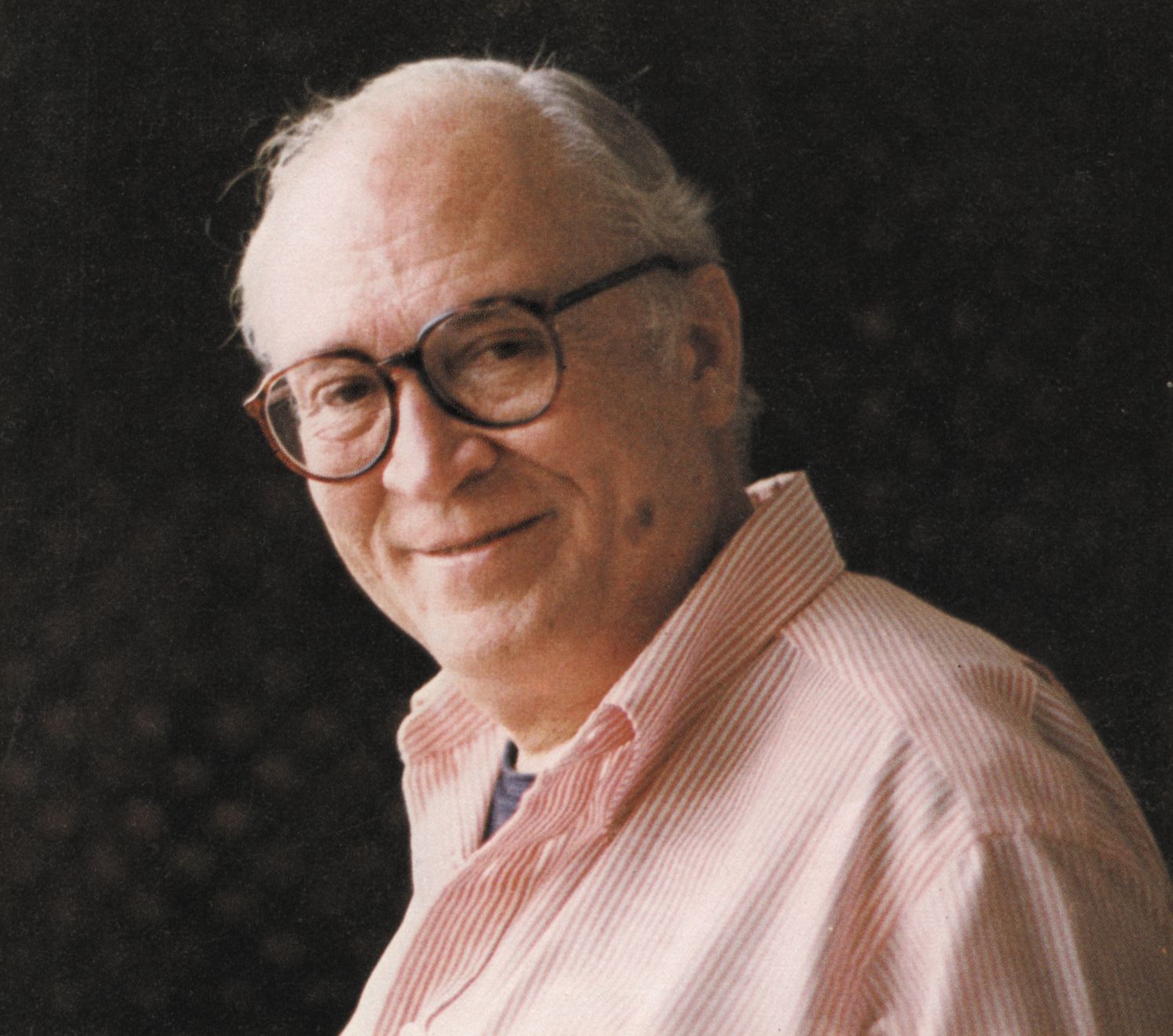

An artist, art educator, and philanthropist: Fernando Zobel had lofty dreams for Philippine art. Tatler Philippines elucidates on the man and his vision.

This feature story was originally titled as Zobel: The Artist and His Dream published in the August 2005 issue of Tatler Philippines.

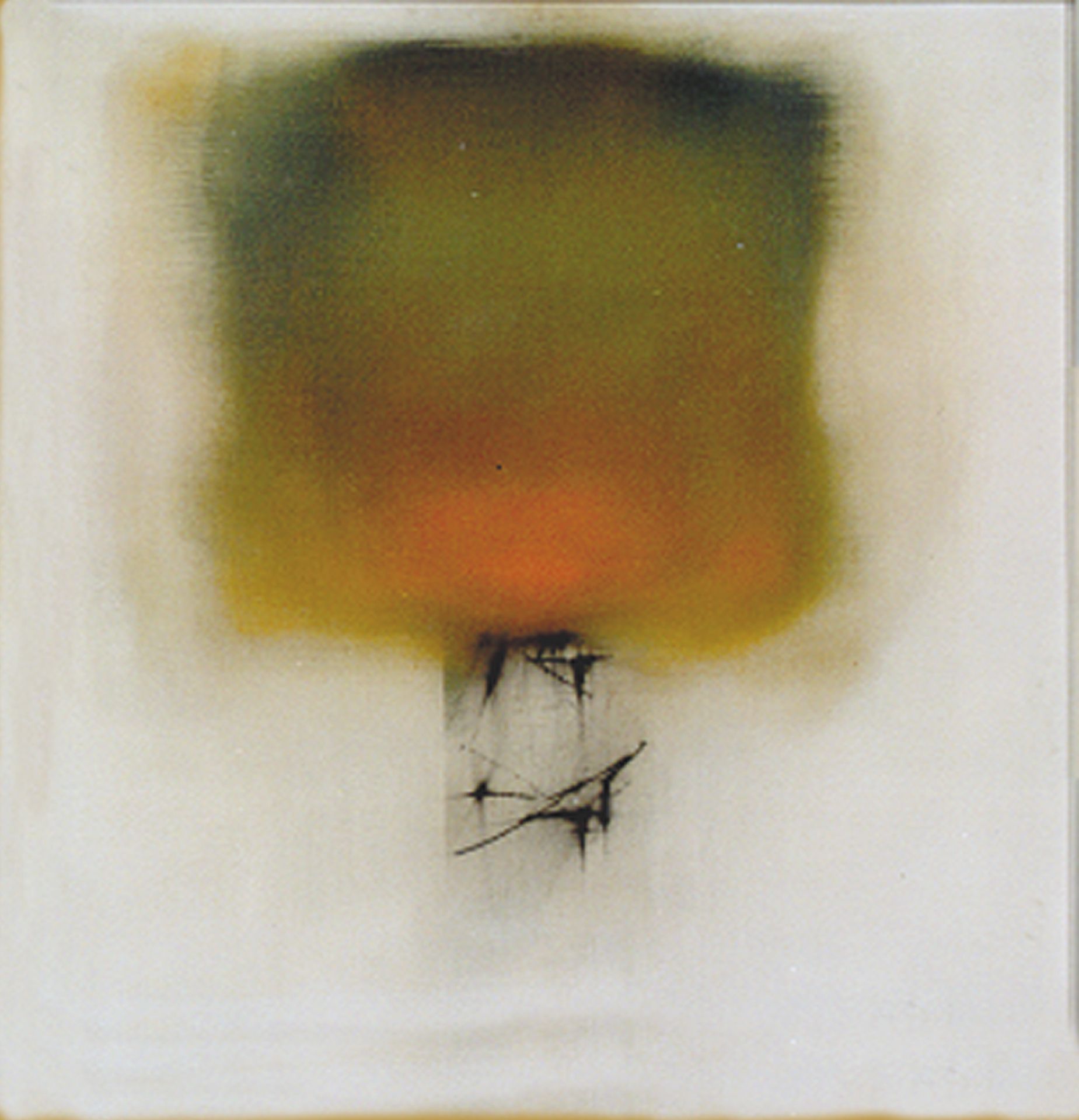

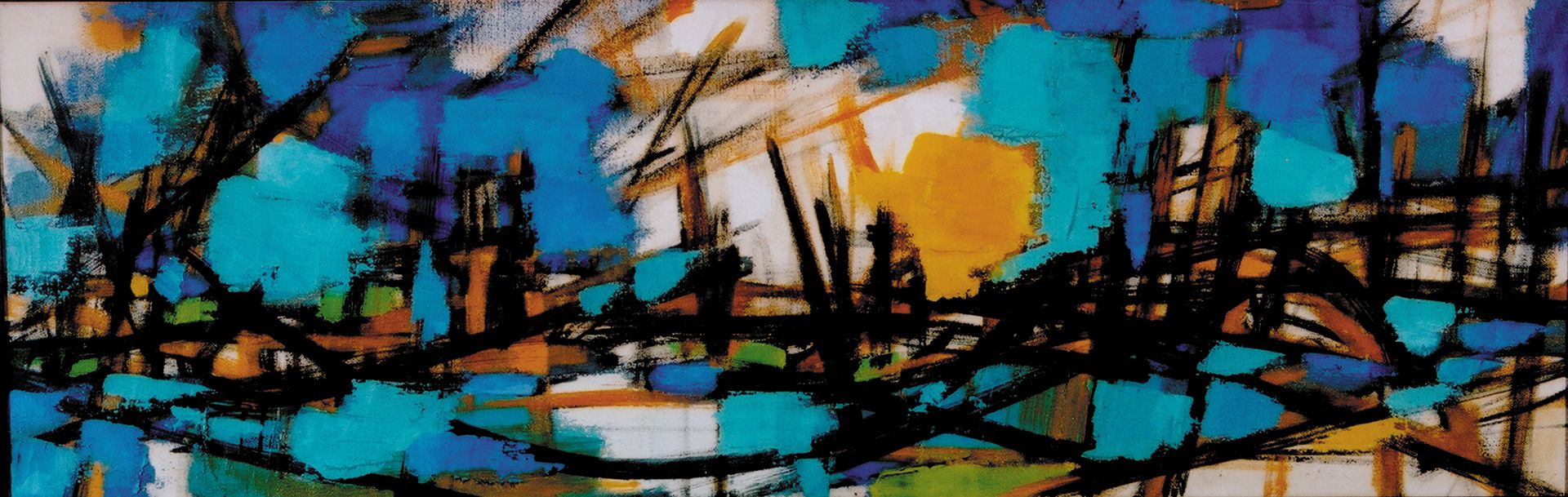

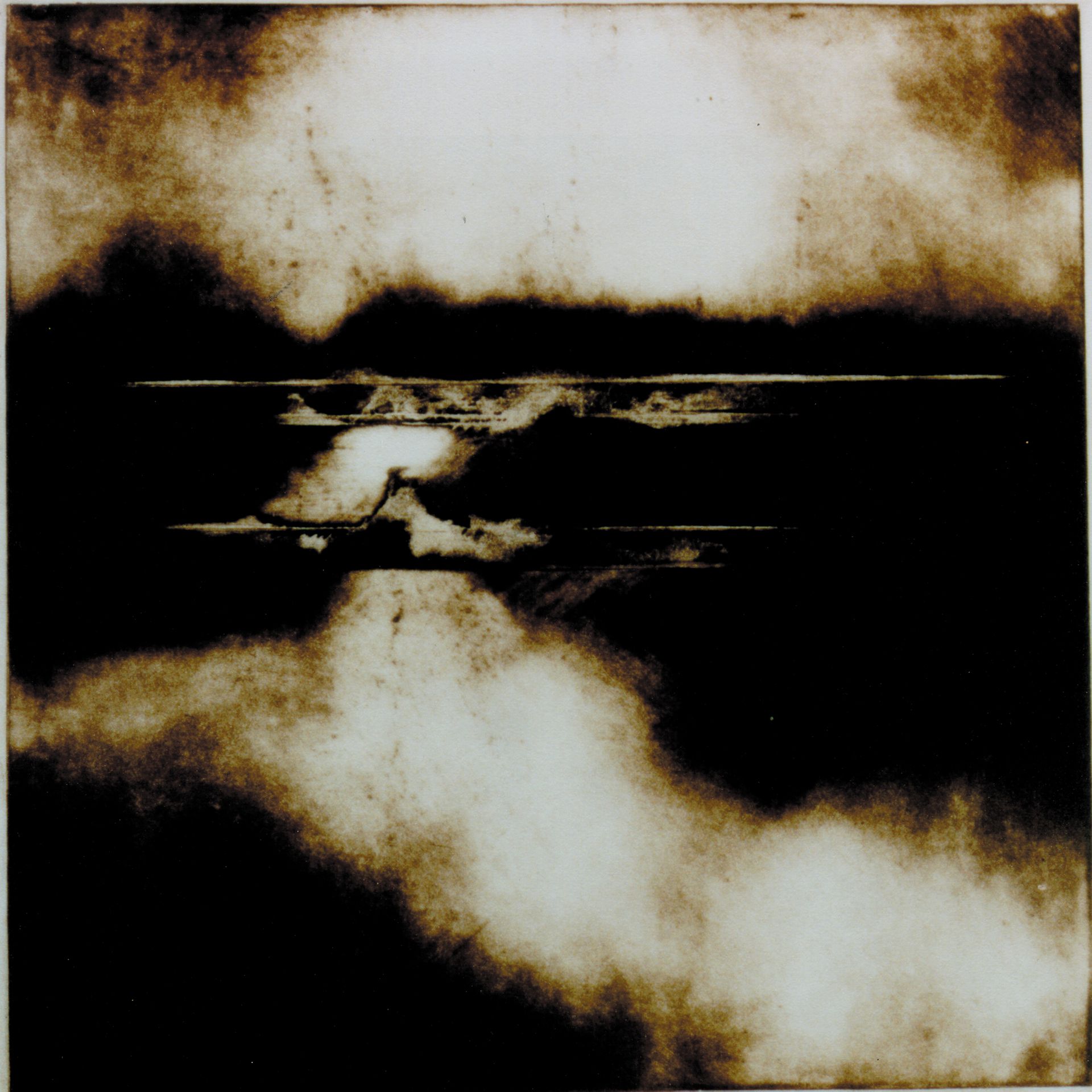

As a child and well throughout the incipient period of his artistic life, Fernando Zobel de Ayala (1924-1984) had one recurring obsession: he dreamed of building a museum that would house his personal collection of Philippine art. His lofty desire to educate a public on modern art, along with his own sympathy for artists who needed help in their art-making, propelled the young Zobel to become a collector. He believed that that the best way to support artists was to buy their works and help them get started in their careers.

More than just an artist, Zobel was known for magnanimity throughout his life, whether it was drawing for the children he encountered on the streets of Spain or obtaining scholarships for young, gifted artists back home in the Philippines.

Zobel belonged to an affluent and influential family well entrenched in the country’s business world. A Spanish citizen at birth, the son of Enrique Zobel de Ayala and Fermina Montojo, he was nine years old when his family decided to move back to their home in Madrid, Spain.

Besides being a successful businessman, Enrique Zobel was a philanthropist and patron of the arts. He was also a skilled essayist who contributed regularly to the newspapers of the day. For his work, he was awarded the Isabel la Catolica del Merito Civil. In his later years, Zobel established the Premio Zobel, a prestigious literary prize that honours Filipinos who have made contributions to Spanish culture. (Don Enrique’s grandnephew and grandniece, Alejandro Padilla and Georgina Padilla de Mac-Crohon are now in charge of bestowing the prize.) It is not farfetched to assume that the young Fernando would have been influenced by the artistic leanings of his father.

When his family returned to the Philippines in 1936, Fernando studied at De La Salle College, and proceeded to pursue a pre-med course at the University of Santo Tomas. It was in 1942, after the outbreak of the Pacific War, when the 18-year-old Zobel developed a spinal deficiency, a lingering ailment that forced him to spend most of the year in bed. While recuperating, he started to sketch, drawing scenes observed through the window, the faces of his family, and things that caught his precocious mind. He also devoted a great deal of his time to reading, realizing later on that he had practically read many of the titles assigned to students in college. He was, in the words of his niece Rocio Zobel, a “voracious reader” and his interests besides painting extended to archaeology, comparative religion, philosophy and art history.

Read also: The Brilliant Life And Turbulent Times Of Don Jacobo Zóbel y Zangróniz