It was probably the best of times, as discovered from unpublished memoirs about a glorious period in Philippine society before World War II

This feature story was originally titled as Glory Days, and was published in the November 2007 issue of Tatler Philippines

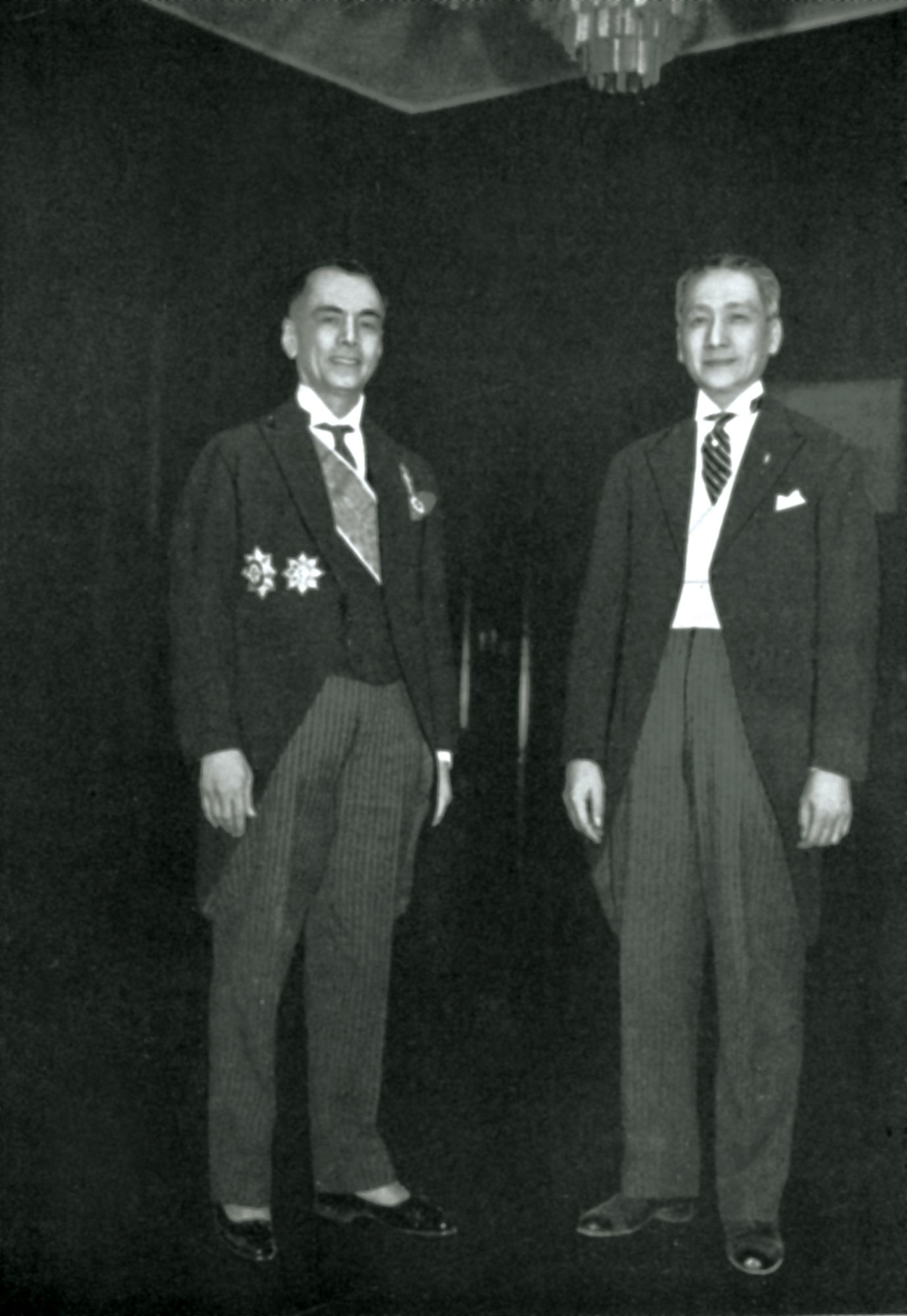

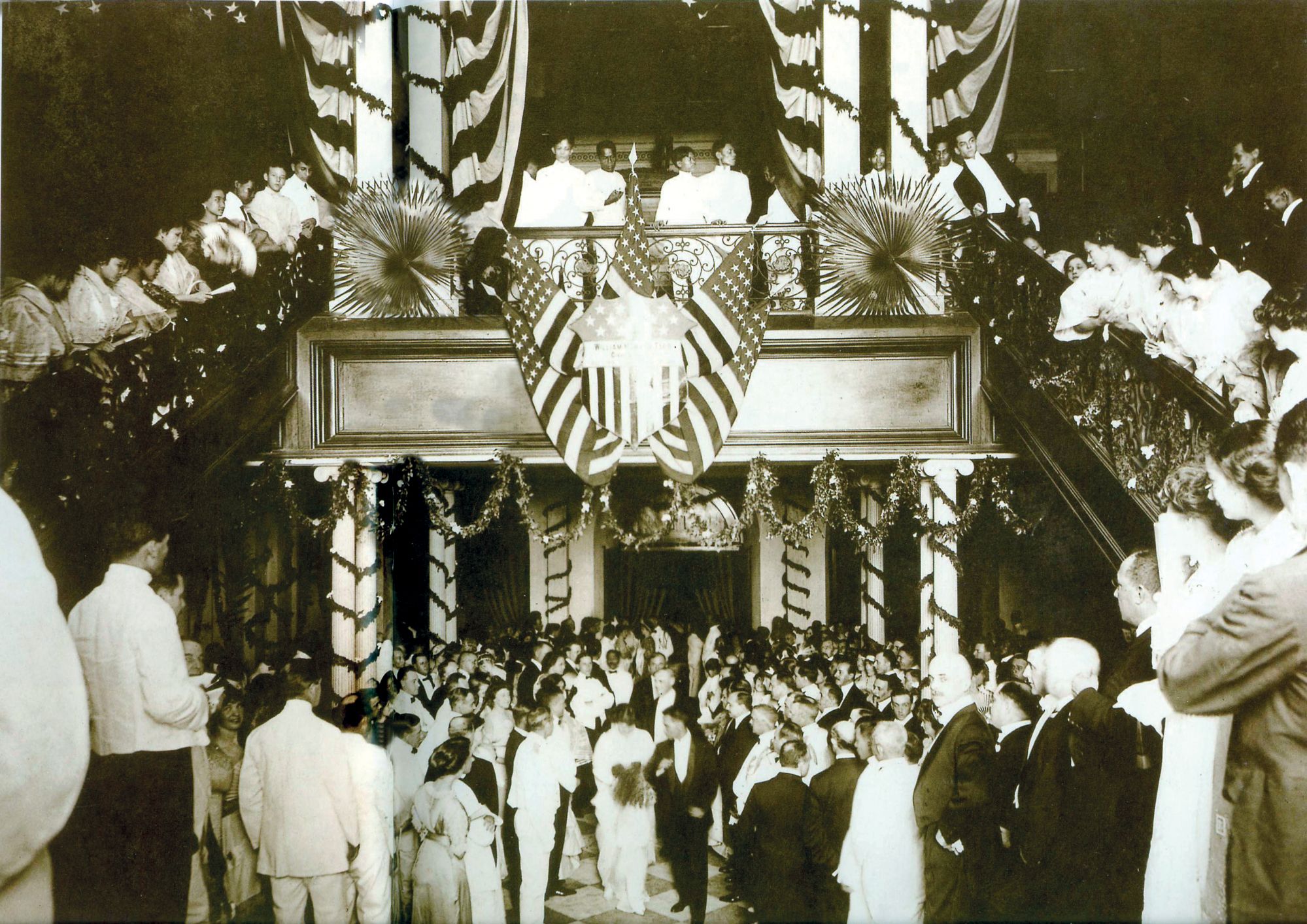

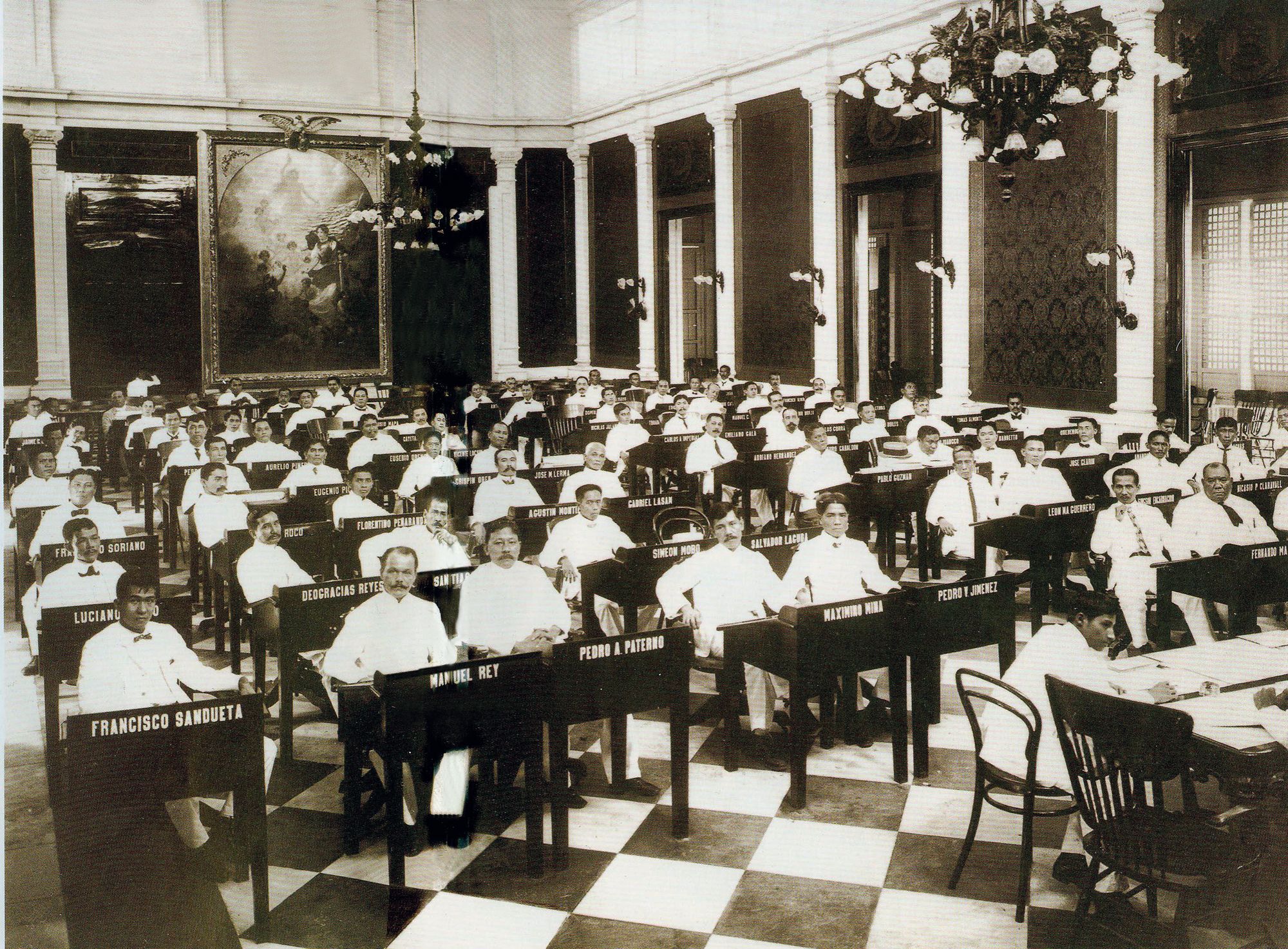

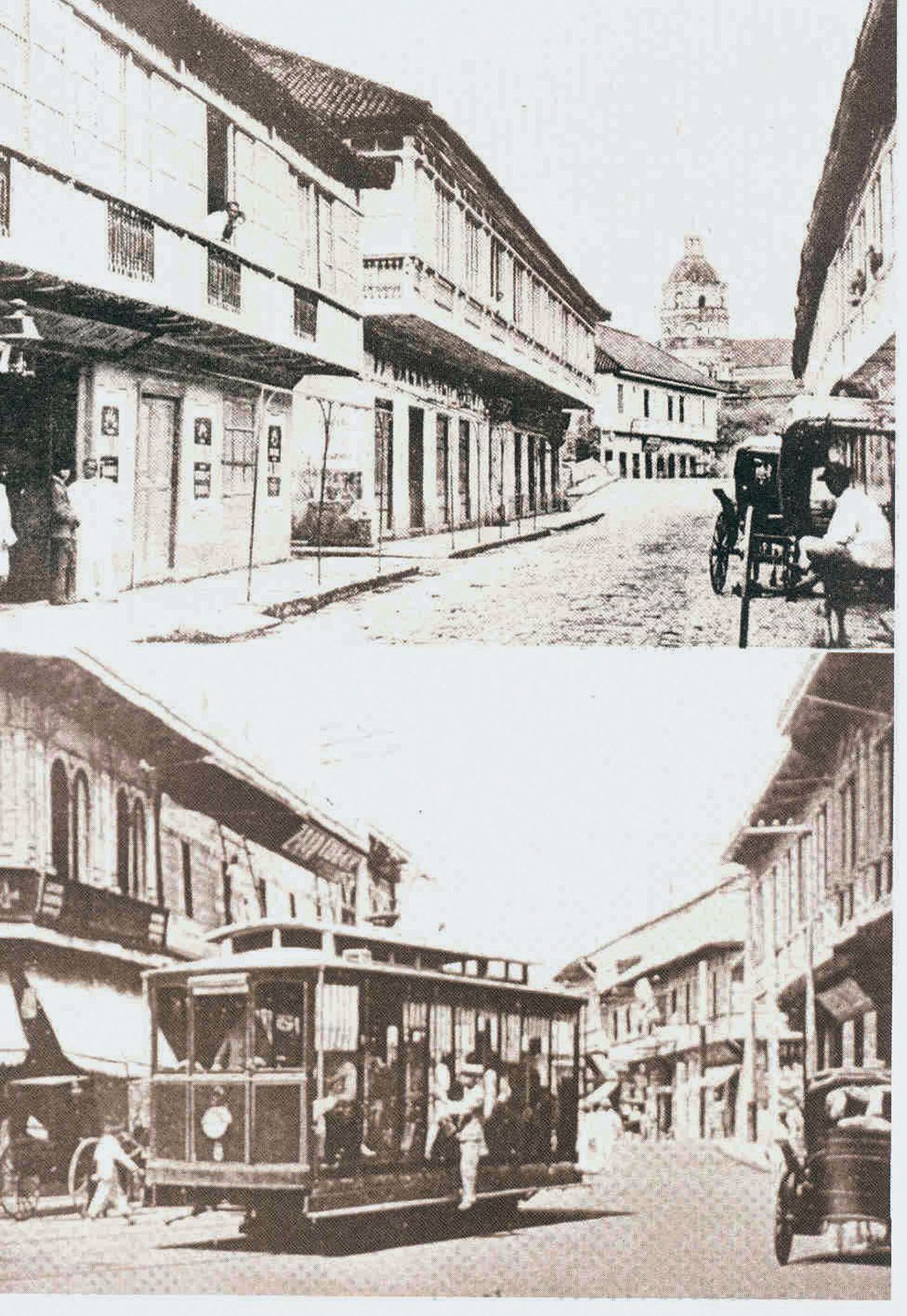

There was a time when Filipinos drove on the left side of the road as other Asians still do today, in Hong Kong, Japan, Thailand and Malaysia. This was in the years before World War II, when Singapore was a British naval base and not much else, Kuala Lumpur was all about rubber plantations, and where what was then the Dutch East Indies with its capital in Batavia (today’s Jakarta) was firmly ruled from the Netherlands. In Saigon the French were firmly in control of French Indochina, and only the recently renamed Thailand could claim any kind of sovereignty. In a region of colonies, only the Philippines had an assurance of independence—and the corresponding self-assurance that made Manila the closest rival of Shanghai in cosmopolitan culture. Besides Shanghai, only Manila could claim a semblance of high society; and that society itself was old, well developed and unique. Manila was closer in atmosphere and culture to Havana than it was to either Honolulu or Shanghai; society, too, was less defined by the colonial masters than, say that of Singapore. It was formal, having an older generation still heavily Hispanic and a young generation highly influenced by American culture.

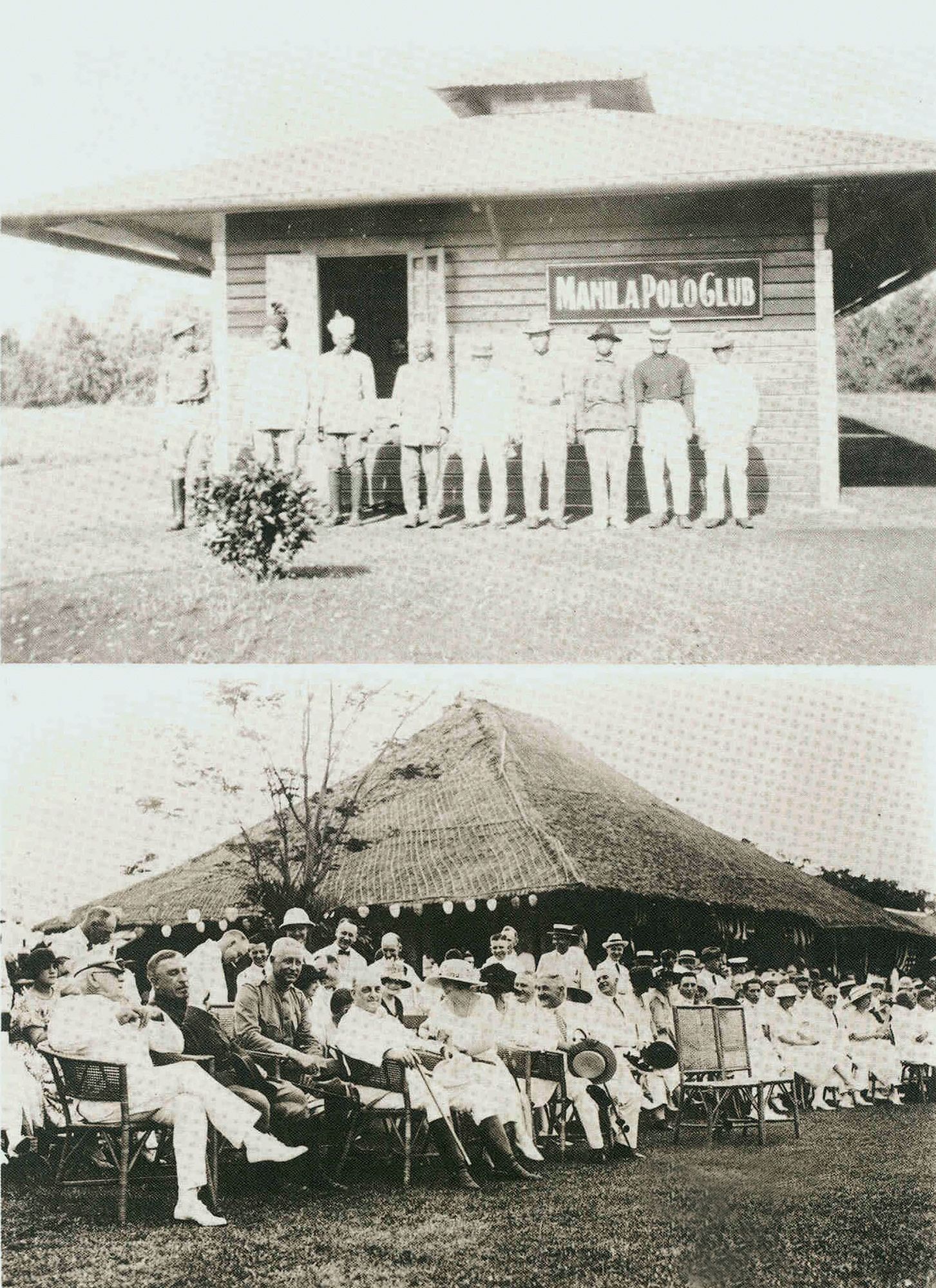

Club, church and school defined society. There were clubs for expatriates: the German Club, the British Club, the Casino Español and the bulwarks of the American establishment: Elks, Army-Navy and Polo clubs. Filipinos who studied in the United States set up the Philippine Columbian (where independence missions were planned and politics avidly discussed). The Trio al Blanco and Club Filipino were the haunts of the gambling set while those bored with cards flocked to the Jai Alai set up by the Madrigals. The ball, featuring the rigodon (type of formal dance), was the centrepiece of the social season; and the cabaret, the hotel and the nightclub defined social places for the young and the old.

The schools, then as now, were the Big Four: La Salle was heavily mestizo (Filipinos with, usually, Spanish or American blood) and Chinese; the Ateneo was not; International School was still known as the American School and Brent strictly didn’t allow Filipinos to enrol. Spanish was the language of the courts and English, that of politics, commerce and the papers.

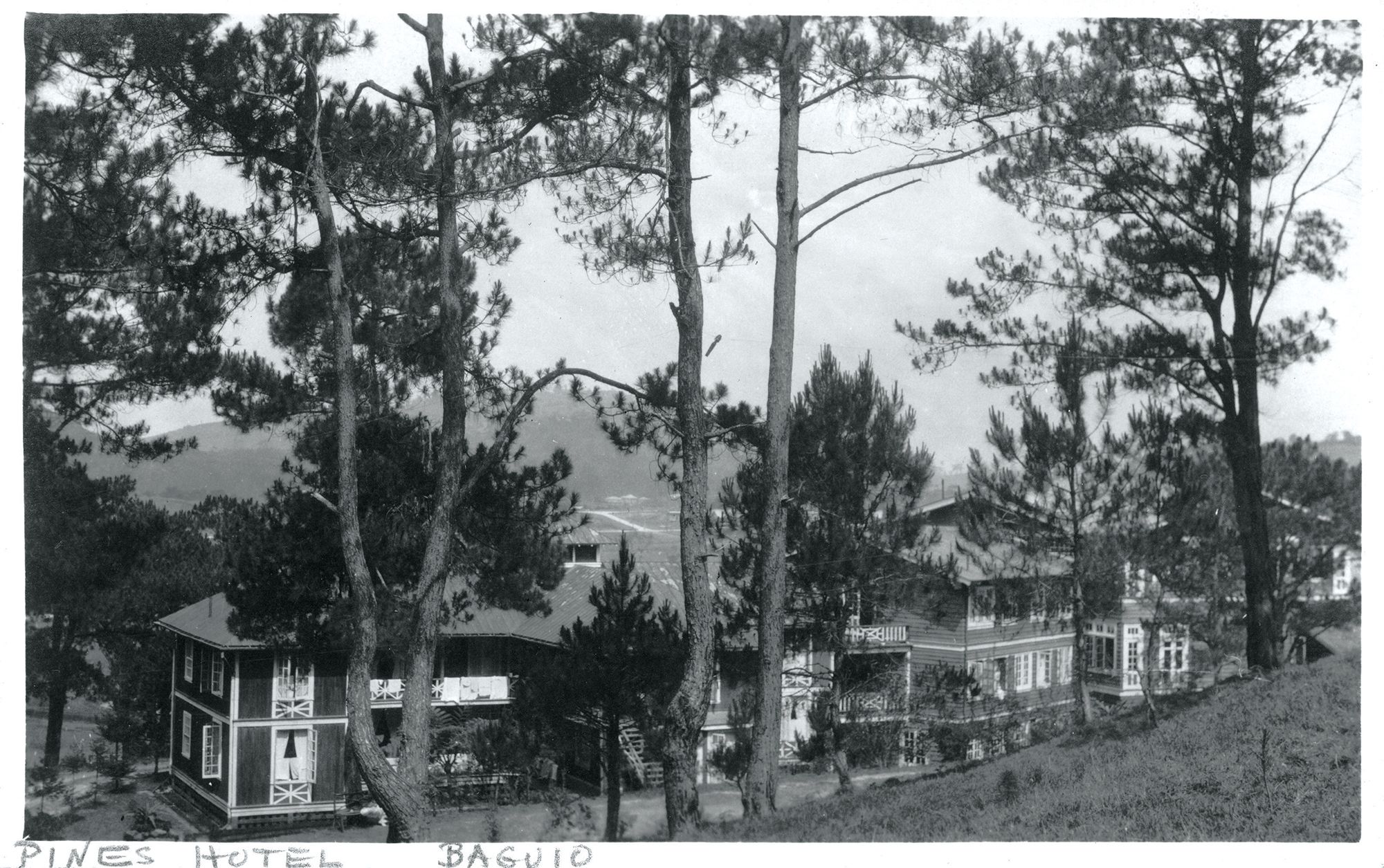

It was a time when the siesta (afternoon nap) was an integral part of the working day, reaching its highest point of refinement (and necessity) in the summer. The season, in fact, would begin with a government order changing office hours, and government and society would decamp to the cool mountain city of Baguio for the duration.